Leonard Frank died last week. He was 82.

The December I was about to turn 24 and living in Northampton, Massachusetts, I took a week long trip to visit my cousin in San Francisco. This was my first time on an airplane, or really on any excursion out of Western Massachusetts, in over 3 years, since I had been bedridden on 7 pharmaceuticals (mostly psychiatric drugs) for the greater part of my 21st and 22nd years.

I had been off of the drugs and involved with the Freedom Center in Northampton for a year, and had finally graduated college. I was just emerging into the land of the living and a more “normal” life after those years of complete isolation and brain fog.

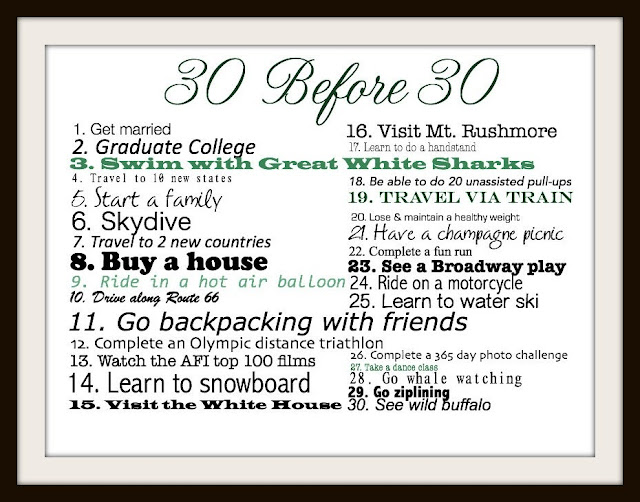

My cousin was living in the Inner Sunset with several of his college friends. They lived in a large apartment with a large poster on the wall about things to do before you turn 30 (they were all 28).

I hadn’t seen the ocean in over 4 years, so I walked there one day, a couple of miles in a city I was unfamiliar with, without looking up directions; I sniffed and sensed my way there, smelling the sea getting closer to me as I walked. I sat there for a long time looking at the ocean. It was a cool foggy day and I was the only one on the beach. I texted a friend from the Freedom Center who I had started a writing group with and sent him a photo of the Pacific.

Getting to the ocean, a whole year after getting off psych drugs, was a marker of my liberation from psychiatry and all the limits and loneliness it preserved in my life those few years. In my year after getting off those seven drugs, I was scared to travel and was on a restricted diet due to blood sugar problems Risperdal had caused me. In order to control my life, I ate certain foods at certain times and primarily ate them alone those few years. When I went out, I brought food with me in tuperware, no matter what, since I had to know what I was eating. My eating habits were isolating but I was scared to give them up because it was food and eating problems that had caused me the most instability in my life right before I started taking psychiatric drugs.

Eating a specific diet was something I clung to for dear life, until it was time to loosen my grip. It took me about a year to feel “normal” about food again.

There I was, a year out of the system, on the beach, certain I’d reached a milestone that only the ocean waves could mirror back.

This is a poem I had written while I was on 7 drugs and in quite a trance:

Now things are well.

They want to know about my journey.

Were there rocks?

Were there diamonds?

How did you sleep on the slants of hills?”

All I have in my pockets is quiet, I say

and open my hand to their ear, to their footsteps.

They want to eat chocolate with me,

and dance.

They don’t know what these things

mean to me.

If you step on a rock, get a degree in diamonds,

You must hold their weight strong in your ear, in your foot steps.

The world is full of brown and retreat,

purple and history,

clear and mystery.

The world is full of Snickers bars and ballerinas,

hospital potatoes, wheelchairs,

writing and waiting

and watching people work

with the wonton of

Want.

It’s been called a wrestle

and wonderful.

I haven’t been waiting.

I haven’t been watching.

I wrinkle at the wonders,

which has been called a withdrawal.

I call it a wrap, a wash.

A friend from the Freedom Center had suggested I meet Leonard Frank in San Francisco, so I called him and later that week accepted his invitation to come to his studio apartment in Pacific Heights and to go out for lunch at La Mediterranee, his favorite restaurant. My cousin seemed somewhat baffled as to why I would be going to meet a man in his 70’s I didn’t know, for no apparent reason. I explained that he was a survivor of forced electroshock and my friend had suggested I meet him. He responded with surprise that forced electroshock ever happened, and seemed to be under the common impression that it was an outdated, hardly used practice.

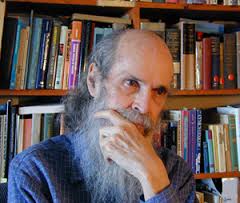

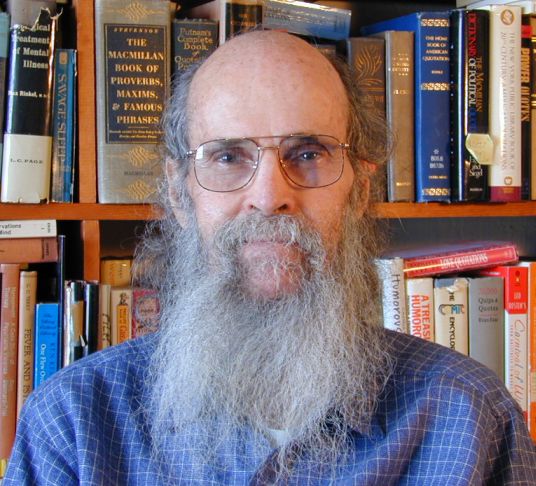

I got directions from him and headed off on the bus to meet Leonard. When I arrived at his apartment, I instantly felt a sense of peace and holiness in his presence. His apartment was full of tall bookshelves, books covering the wall space, and his desk with a large computer.

He told me about his experiences as a young adult, being force shocked over and over at the age of 30, and how, upon exiting the mental health system, he had huge gaps in his memory from his life before 30. He couldn’t remember a lot of his childhood and a lot of things he had learned over his life, but he was determined to relearn as much as he could, and build back his mind.

Leonard spent most of his time, for decades, reading. In order to help himself remember, retain and synthesize information, he kept a database of quotes and passages that were relevant to him. For days and days, years and years, Leonard collected these lines and paragraphs. He eventually put together a Quotationary, a dictionary of these lines, published by Webster. He said there was still quite a bit of his memory he never recovered, and I could tell he had deep grief about this, this permanent loss. When I offered the idea that anything is possible, implying that it might be possible for his memory to come back, or for anything at all to happen, really, he insisted I was wrong. We a had a moment of holy disagreement where I said anything is always possible and he stood strong that some things are permanently lost, nothing can bring them back.

He was a literary soul, he wanted to remember his life.

Psychiatry for a literary soul misses the mark. This is why so many who escape psychiatry have a passion for words, memories, storytelling, blogging, writing books, reading. We have this awareness that so much of life is in the telling and that storytelling can limit us forever, or it can freshly liberate us in each passing moment.

Leonard didn’t merely spend all of his time reading, writing and walking around his neighborhood because those were his favorite things to do. Perhaps they were, but he was also liberating himself from psychiatry everyday. His simple life of reading and finding the truths that were true for him was a stand he took for his spirit, for the spirit of so many of us.

I think of Leonard as a monastic; he never owned a car, was vegetarian his entire life and spent almost all of his time studying, contemplating and collecting deep truths. Like a monk, you could feel this in his presence. He was spacious to be around, it was easy to breathe while talking to him.

As a literary soul myself, who spends hours a day writing and walking around my neighborhood, wherever I may live, it’s clear to me that literature is cornerstone in resisting oppression of all kinds. By reading and writing, we keep our minds agile and able to see things from different angles and labeling ourselves or others has very little, if any, place. A literary soul will naturally discard psychiatry with its oversimplifications and attempts to “cure” our complex genius, always hiding underneath any madness.

Leonard was a mad genius in the very best sense-he was devoted to truth and justice, a maddening pursuit, but one that always leaves a legacy, always leaves people remembering and crying when the “madman” is gone.

When I returned to my cousin’s place that evening, he asked about my day and I didn’t say much. On the wall was still the list of things to do before you turn 30.

Thanks Chaya. I truly loved reading this, and I’m so glad you took the time to write it.

Thank you so much Molly! It meant a lot to me that you were there to talk on Saturday. You really helped me get through a tough day, a very sad time. Thank you for listening, and for reading this.

Beautifully written Chaya.

Thank you so much Jim. Both yours and Leonard’s presence in the movement has meant so much.

Fantastic! You captured him very well.

Thank you Wade, and thank you for putting together the memorial for Leonard. It will be nice to meet you there.

Dear Chaya,

This perfectly captures how it felt to be with Leonard. Your words are beautiful. Thank you.

Thank you Dorothy. I still remember the beautiful talk the two of you gave at NARPA in LA. I may be wrong, but something tells me you will find a way to make it to his memorial. In any case I know you will be there in spirit. <3

Hey Chaya.

It was a pleasure meeting you this past Saturday to remember Leonard and I appreciate your reflections here. Stay cool!

Thanks Dan! You too. That was a special memorial and day and I haven’t been the same since. Went back to Leonard’s apartment today to gather more books and stuff. I’ve been reading through Leonard’s quotation books this evening–Gosh, I didn’t realize how great they were. Why didn’t I read them sooner?

Great quotes from a great compiler and editor! I’ve been lucky to have been reading his collected quotes and personal aphorisms for years. So much wisdom it’s sometimes boggling, yet sometimes so simple and obvious. That’s their beauty.

Yes, and I love how he didn’t take sides, but shared such a variety of viewpoints in his quotation compilations 🙂

It is surely the obvious that we need to be reminded of the most.

As a result of its engaging gameplay loop, enjoyable mechanics, and capacity to entice players to return for another run, snow rider has become popular despite its diminutive size.

متاسفانه بسیاری از اکانتهای ارزانقیمت تریدینگویو که در بازار فروخته میشوند، تریال یا کرک شده هستند و خیلی زود مسدود میشوند. اگر میخواهید تحلیلهایتان حفظ شود و اکانت شخصی خودتان را داشته باشید، پیشنهاد میکنم سرویس اکانت قانونی تریدینگ ویو سایت شوپی را بررسی کنید. این اکانتها کاملاً اورجینال هستند و بدون قطعی یا مشکل پریدن اشتراک، تا آخرین روز فعال میمانند.

من از گرافیسو یه پکیج کامل مدارک کشورهای مختلف گرفتم و باورم نمیشد که اینقدر واقعی طراحی شده باشن. آیدی کارت و پاسپورت ترکیه و انگلستانش دقیقاً مثل اصلن. پکیج مدارک بینالمللی گرافیسو واقعاً برای کسانی که دقت، کیفیت و جزئیات براتون مهمه، بهترین گزینه است.

This article provided clear and useful information. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us. Speaking of useful tools, want to create fun caricatures from photos? Check out Caricature Maker Online , a simple online caricature generator with instant results.

Thanks for this helpful post. The information is clear and valuable. I hope to see more updates soon. Speaking of useful tools, want to create fun caricatures from photos? Check out Caricature Maker from Photo , a simple online caricature generator with instant results.

Thanks , I have recently been searching for information about this subject for a long time and yours is the best I have found out so far. But, what concerning the bottom line? Are you positive about the supply? Of course, if you want to play a fun browser game, check out Rocket Goal Game – it’s free and requires no download!ocket Goal Game – it’s free and requires no download!

I think this is among the most vital info for me. And i am glad reading your article. But should remark on few general things, The website style is ideal, the articles is really nice : D. Good job, cheers Of course, if you want to play a fun browser game, check out Rocket Goal Car Game – it’s free and requires no download!tgoal.app/”>Rocket Goal Car Game – it’s free and requires no download!

Thanks for the clear and helpful breakdown. The content is valuable and straightforward. Keep it up. Speaking of useful tools, want to create stylized AI graffiti from text? Check out graffiti font generator , a simple online graffiti generator with instant results. results.

Great post with clear insights. The content is practical and easy to understand. Keep it coming. Speaking of useful tools, want to create stylized AI graffiti from text? Check out graffiti tag alphabet , a simple online graffiti generator with instant results.

This is a helpful and well-written piece of info. I’m glad you shared it with us. Please continue to update us like this. Thank you for sharing. Of course, if you want to create a unique avatar, check out square face generator como usar – it’s a fun tool!un tool!

This is a nice and well-explained piece of information. I’m glad you shared it with us. Please keep us updated. Thank you. Of course, if you want to create a unique avatar, check out how to input rgb square face generator – it’s a fun tool!!

Great read! The points you made were clear and very useful. Appreciate the share! Of course, if you want to create a unique avatar, check out group hardcore ironman world oldschool runescape reddit – it’s a fun tool!

Great job on this! Helpful and easy to understand. Thanks! Of course, if you want to create a unique avatar, check out tft world of runes – it’s a fun tool!